| Previous Report | All Reports | Next Report |

Three months we have now spent on this tour in the Balkans; counting Tizian’s previous tours and travels, it is now even a total of about eight months for him. Therefore, we thought, we put together a few highlights along our bicycle tour and travel routes.

We want to put the focus on beautiful and especially spectacular route sections for bicycle travelers (most of them are certainly also interesting for motorized travelers) and garnish the whole thing with a few worth seeing cities and other places that perhaps not everyone has immediately on the screen. To save us some work, we especially left out cities like

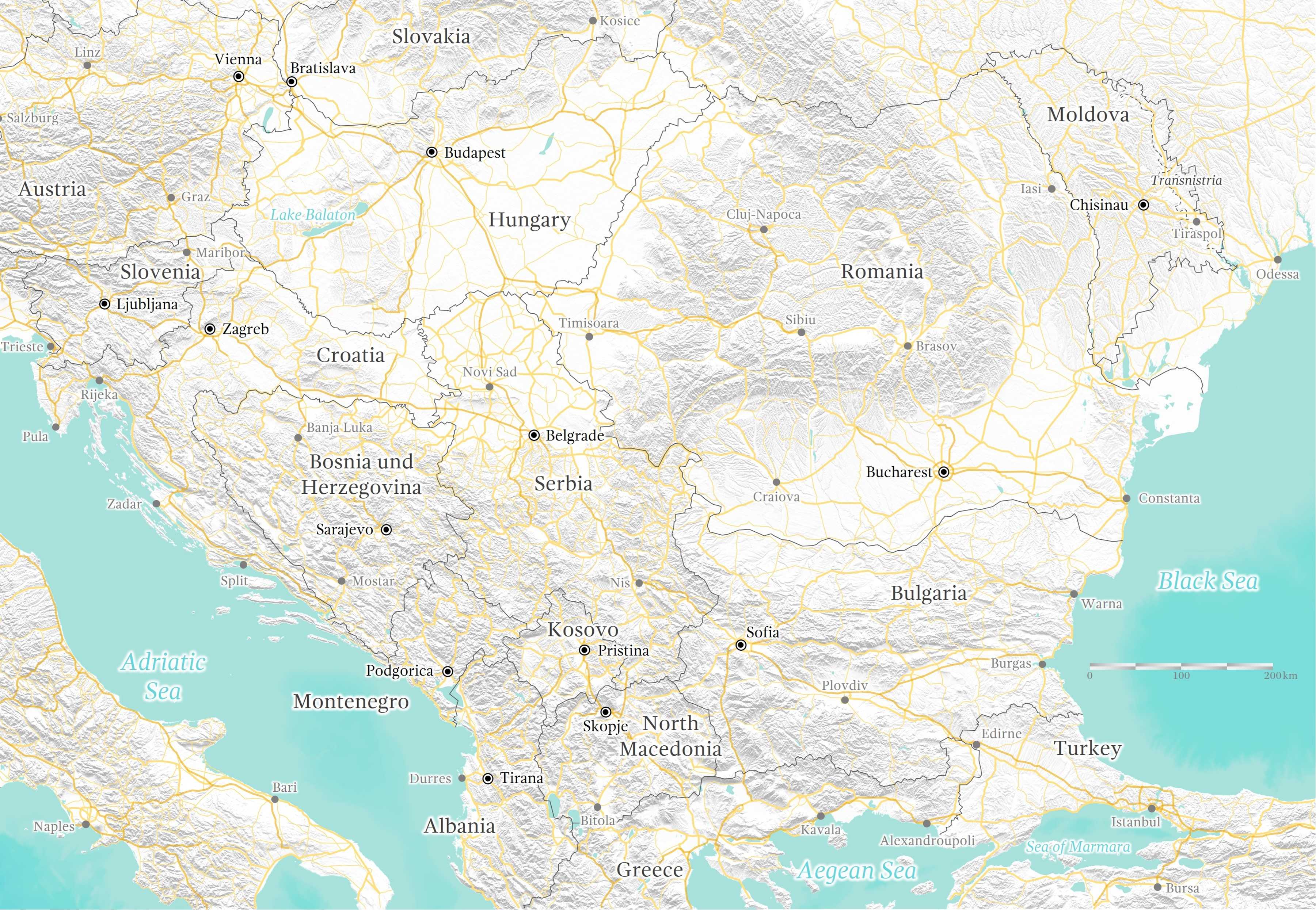

In addition, we must of course limit ourselves to route sections and places worth seeing that we have actually already visited ourselves – about others, of course, we can say nothing. The map below shows in gray lines, which travel routes by bicycle (solid line) or car (dashed line) we can cover in the Balkans. Apart from these, however, there are certainly countless other interesting destinations.

Beautiful Route Sections

Many people cycle from Central Europe in the direction of Istanbul, but only a few choose the route through the Montenegrin hinterland. From our point of view, this mistake should be avoided at all costs.

From what we have read, heard and seen, the route through the Piva Canyon must be the most spectacular in the entire Balkans. The road runs along the steep slope of the canyon, or – given the no less than 68 tunnels blasted into the rock without a lining over a distance of 21 kilometers – actually rather through them.

In addition, the route is extremely varied: Coming from Bosnia and Herzegovina, the road leads at the beginning halfway up the rock face about 50 meters above the river until you reach Europe’s highest dam outside Switzerland. This dams up the Pivsko Jezero, so that the second section of the road lies directly on the turquoise-blue water. If you turn left about two kilometers north of Plužine, you reach an even smaller, but still paved road that winds upward in several switchbacks along the steep slope, trying to escape the gorge and reach the plateau of the Durmitor massif. The further you climb the wall of the gorge, the more breathtaking is the view of the lake below and the surrounding peaks.

Around Lake Shkodra there are basically three roads leading to the southeast: A road on the north shore, a road on the south shore and then the road along the Adriatic coast. The latter is comparatively large and heavily traveled, and also touristy due to its proximity to the coast. The former allows a view of the lake only on short sections.

If you have to decide on a bicycle tour here, we can only recommend the route along the south bank. The road is properly asphalted, but very narrow and hardly used – you could almost call it a bicycle path. The south shore of Lake Shkodra is much more mountainous than the north shore and so you usually ride high above the lake and have a fantastic view of the water, especially in the many places where the slope is rocky and barren. Nevertheless, there is also the possibility to ride the 400 meters of altitude down to the lake to swim in the lake at fine pebble beaches.

You should not shy away from altitude difference if you choose the road southwest of the Fierzë reservoir. And you should also bring time with you, because if you want to take this road for the approximately 40 kilometers as the crow flies from Dushaj to Kukës, you will end up with triple that on your speedometer – that’s how much the road winds and twists (horizontally and vertically) along the steep slope that borders the Fierzë reservoir.

But the whole thing is definitely worth it! The road is mostly excellently paved and the car traffic tends to zero, especially in the northern section (Dushaj–Shëmri). And even if the lake itself is often hidden behind mountainsides and trees, the views are always breathtaking!

A small, bicycle path-like, excellently paved road that winds through lush green grass in moderate gradient – at least considering the altitude: This is what awaits you here on the Durmitor massif. All around rocky mountains over 2000 meters high stand trellis, the road itself reaches its highest point at around 1900 meters. It is probably one of the few paved roads in the region that takes you above the tree line, allowing for very special views. Anyone who wants to venture into mountaineering territory by bike should take a closer look at this road.

From our point of view, the Tara Canyon is not quite as spectacular as the Piva Canyon; if you have cycled through the Piva Canyon directly before and have raised your expectations accordingly, you could almost be a bit disappointed. But that would definitely be doing the Tara Canyon an injustice; it, too, impresses with a rushing river in the clearest turquoise, with steep rock faces and with asphalt that is full of holes from falling rocks. In addition, the Đurđevića-Tara Bridge is a real eye-catcher, which is so missing in the Piva Canyon.

The tourist infrastructure (campsites, rafting, zip lines) is noticeably better developed in the Tara Canyon, but at the same time there’s a bit more traffic in the Piva Canyon. But it does not have to be either-or: After all, you can combine both canyons wonderfully.

The mountains in northeastern Albania are impassable and sparsely populated – and that, of course, is exactly what makes them so appealing. If you want to take it to the extreme, turn right on the road from Kukës to Peshkopi after about 15 kilometers and you will find yourself on an unpaved road that leads directly along the Black Drin.

The road quality is extremely variable and over large parts, to put it mildly, a challenge. In addition, there are three steep descents and two no less steep climbs. But that’s what you call adventure.

You cross the Black Drin twice on rusty bridge frames lined with wooden planks and usually have to stop briefly to admire the spectacular scenery and wilderness, because riding the road demands full concentration. Still, it’s rarely the easiest roads that pay off the most!

Admittedly: Most of the Greek Aegean coast between Kavala and the Turkish border is not overly attractive. Insofar as you are on the road here, you should be all the more careful that you do not miss at least this little piece. Because that can happen quickly if you navigate with road maps and shy away from non-asphalted roads.

Even if many road maps might hide it: The mountain on the coast between the villages of Maroneia and Dikella can also be cycled around on the south side. Here there is a small gravel and sand road that leads through a rocky landscape, where only scattered olive trees provide shade. If one does not look at the fact that they are olive trees, it reminds a little of the outback of Australia.

If you don’t have the narrowest tires on, the path should be easy to pass by bicycle; still, it’s a lonely spot. Although at the time we didn’t ride down to the lonely beaches to the sea and camped there, but probably that was a mistake. But even so, the desert-like landscape and the views of the Aegean Sea remained extremely positive in memory.

The Morača Canyon is the deepest of the canyons in Montenegro and of course correspondingly impressive. Unfortunately, the road was relatively busy in 2013 as it carried the main traffic load between Serbia and the Montenegrin coast. Fortunately for future bicycle travelers, this has probably improved now that the parallel highway has been completed with Chinese help. Unfortunately, we only found out about it afterwards on this tour, after we had decided on an alternative route (which, however, leads through the Cijevna Canyon on the Albanian side of the mountains, which is worth seeing, so we don’t regret it too much).

After all, the heavier traffic in 2013 made the Morača Canyon notorious not only for the scenery, but also for the frequent accidents. For those lucky enough not to be involved in one, this fact is nevertheless noticeable due to the mass „Auto Šlep“advertising stenciled and graffiti sprayed on rocks, guardrails, signs and also directly on the road.

It’s quite possible that this route would have earned a much better place nowadays in view of the lower traffic. But since we have had no firsthand experience in this regard, we are left with a very respectable eighth place.

It takes a certain amount of masochism to cycle the Drežanka Canyon (between Blidinje Jezero and Neretva). Because there it goes almost 1000 meters on a really bad gravel road very steep downhill (or uphill in the other direction). This is neither efficient nor easy on the bike, but you can be sure that only a few people will enjoy the magnificent views of the Drežanka Canyon from this road with its countless serpentines.

The Cijevna Canyon is an alternative to the parallel Morača Canyon and when the latter was still busy (i.e. before the parallel highway was completed, which greatly relieves the Morača Canyon) it was possibly also the more bicycle-friendly option. However, at that time it was not yet asphalted throughout.

Today it’s different: Fresh asphalt leads from the Montenegrin border at Gusinje to Lake Shkodra or, if you follow the gorge across the recently opened border back to Montenegro, to Podgorica. The course of the road is like a roller coaster: there are always short, very steep sections and tight curves, and the road is usually quite narrow.

The canyon is partly only sparsely overgrown, the mountain slopes often consist of bare rock. On hot summer days, you can cool off in various places in the Cijevna and then often swim through small miniature canyons past steep rock walls several meters high.

The landscape on the banks of the Danube is possibly beautiful, but not particularly spectacular, practically along its entire length. However, there is one exception to this rule: the Iron Gates.

The Iron Gates are the canyon with which the Danube breaks through the Carpathians. In this vicinity of the mouth, the Danube is normally about one kilometer wide. The Iron Gates, however, cram it down to as much as 200 meters; the river is therefore over 50 meters deep in places.

In the Iron Gates, the Serbian-Romanian border runs directly in the middle of the Danube, and a road runs along both the Serbian and Romanian banks. Which one is more suitable for cycling, we cannot judge; probably a little less traffic would be quite pleasant on both sides. However, the views down into the Danube gorge make up for this shortcoming.

The Bay of Kotor fulfills all the characteristics one expects from the Adriatic coast: touristy, expensive, a lot of traffic. However, if you’re not afraid of a challenge, you can escape it and probably get the best view of the bay in the process.

No less than sixteen 180° serpentines are necessary to overcome the 500 meters of altitude. Since the first serpentine is already at 400 meters, you finally come out at 900 meters above the bay and can watch the cruise ships docking in Kotor. And all this from a safe distance, far away from everything negative that mass and cruise tourism brings with.

Many roads lead you from the north of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the direction of Sarajevo or Mostar, but you have to be careful not to find yourself on a narrow road through a narrow gorge, where many trucks and cars also want to come south. A very scenic alternative is the route Martin Brod–Drvar–Glamoč.

North of Drvar the road is framed by bushes, between Drvar and Glamoč bushes grow only sporadically and wide grassland prevails. It is generally one of the most sparsely populated regions of the country and thanks to the lack of trees and bushes you can see that here too: not a soul for miles.

The road is unpaved in sections between Drvar and Glamoč, but when we were there it had just been re-rolled and was accordingly quite smooth to ride on. Of the many north-south routes in Bosnia and Herzegovina, this is certainly one of the most beautiful.

The special thing about this road is that it practically runs along the ridge of the mountain and thus does not just overcome one saddle point, as other pass roads usually do. This leads to the fact that in some places you can look down into the parallel valleys on both sides of the road at the same time. For a well paved, not overly steep road, this is quite unique. And thanks to the parallel highway that runs through a tunnel at the bottom, there is almost no traffic on this road.

From Tirana to Lake Ohrid there are three alternative routes: The northern route (Tirana–Bulqizë–Debar–Struga), the middle route (Tirana–Elbasan–Librazhd–Prrenjas) and the southern route (Tirana–Elbasan–Gramsh–Maliq–Pogradec).

The northern route has its charm between Tirana and Klos, but otherwise, just like the middle route, it is comparatively boring and also leads over the larger roads. And if you don’t necessarily have to move as fast as possible, there’s really no reason to choose the middle route.

Especially for cyclists, the southern route is definitely the best choice: it leads over the roads with the least traffic and through the most beautiful landscapes and is mostly well paved (only a few kilometers west of Maliq are gravel). It runs along the Banjë and Moglicë reservoirs and through narrow, rocky gorge sections of the Devoll River. Although the route follows the Devoll River almost continuously after Elbasan, it does not spare you from steep sections, e. g. to overcome the difference in height of the dam walls. But this also allows for ever-changing perspectives of the river and the lonely mountain landscape.

The highway along the Croatian Adriatic coast, the “Jadranska Magistrala”, is considered one of the most picturesque coastal roads in the world. The coast is mostly rugged and mountainous, the road correspondingly winding and the views of the Adriatic Sea and especially the islands off the coast are really worth seeing.

Nevertheless, I would personally recommend this route for cyclists only limited. Due to the widespread tourism on the Croatian coast, the road is busier than would be pleasant. In addition, there are generally higher prices (especially for accommodation) and a more difficult wild camping situation. Like everywhere else in the world, the friendliness and open-mindedness of the local population decreases as tourism increases. In all these respects, the Croatian hinterland is the exact opposite: low-traffic roads, reasonable prices, diverse wild camping opportunities, and very friendly people. In my opinion, one should not be so blinded by the radiance of the Jadranska Magistrala that one overlooks the advantages of the Croatian hinterland.

Cities Worth Seeing

From the Istanbul Tour 2013, Tirana is remembered as the most un-European city on the tour. Here, the streets were in the greatest chaos, the curbs were the most broken, the paths the dustiest, and the mess of power cables running above ground through the city, from where everyone apparently just puts a line into their own house. The first modern high-rise, the TID Tower, was just under construction in 2013.

Since then, the city has cleaned up quite nicely. The central square has been cleaned up, streets have been transformed into pedestrian zones, dusty, littered meadows on traffic islands have been turned into tidy parks with trees and benches. And next to various new high-rise buildings, the TID Tower now virtually disappears. Whether these changes make the city more beautiful from a tourist point of view or more boring and interchangeable is a question of taste.

The contrast between the socialist boulevard and the modern center with its main square and park, between rather shabby side streets and modern high-rises, between expensive trendy bars in the hip government district and the very inexpensive restaurants a bit outside of it, however, still make the city very worth seeing from our point of view.

Tiraspol is the capital of the de facto regime Transnistria, a Russian-dominated breakaway part of Moldova. De facto regime means that Transnistria is not recognized by any other state in the world, but in practice it is a completely independent state, with all that this entails: its own border security and entry regulations, its own police, its own currency. Although Russia does not recognize Transnistria as an independent state, it still supports the regime militarily, among other things.

In Transnistria, they say, the Soviet Union is still as alive as not even in Russia anymore. Since I have never been to Russia (and, by the way, not to the Soviet Union either), I cannot judge that, but at least parts of the architecture, the oversized statue of Lenin, the uniforms of the border police and the ancient trolley buses come very close to my idea of the Soviet Union.

Besides various monuments (and old tanks) and the general Soviet flair, a few kilometers south of the city there is the Kitskany monastery. If you are a little persistent and leave a few rubles as donations, the monks will let you climb up the tower.

Transnistria is not a country like any other and thus the capital Tiraspol is not a city like any other. Both are definitely destinations that will be remembered for a long time.

It may be that some people don’t find anything special about the city and dismiss it as another boring, touristically insignificant capital of a small country. But I really liked it. It has beautiful, cozy parks to offer and many of the streets are lined with avenues, making the city surprisingly green. I also have positive memories of visiting restaurants in the city (especially this Georgian restaurant). For me, it was the perfect city to rest a bit at the end of a long trip.

But if you want, you can also immerse yourself in a hustle and bustle that has no equal: First, there is the large market, where you can buy everything, really everything possible (for example, a 2 × 10 meter plastic tarp to wrap your bike for the return flight). And then there is the bus station. The entire public transport in Moldova is handled by white Mercedes Sprinter minibuses, and so countless of these vehicles are parked in the parking lot of the bus station, entering and leaving it every second.

Skopje is definitely an extraordinary city. Whether in a positive or negative sense, opinions may differ, but as such it undoubtedly has tourist value, at least if you know the background and can classify it.

Since the ancient Macedonia of Alexander the Great, there was no country “Macedonia” until after World War II, when a separate constituent republic was created under this name within socialist Yugoslavia. And also the Macedonian people was practically reinvented at that time, because only after that the population of the area was no longer considered as Bulgarians or South Serbs, but just as Macedonians. After independence in the context of the disintegration of Yugoslavia, the Macedonian nationalist party VMRO-DPMNE began (during the periods when it was in power) to refer again to ancient Macedonia and to impute a great ancient past to the small, young, Slavic state. And all this much to the annoyance of Greece, which considers the ancient Macedonians as Hellenes. Moreover, large parts of the geographical region of Macedonia are still on Greek territory today and Greece fears territorial claims from Macedonia (more about these backgrounds in podcast episode 10).

However, this did not stop the VMRO-DPMNE in 2010 from initiating the Skopje 2014 project, in which the country’s capital was to be completely transformed. Facades of representative buildings were redesigned according to antique models and provided with Greek columns and a vast number of statues of more or less well-known Macedonian painters, authors and musicians were erected as well as of the Byzantine emperor Justinian I or the Bulgarian tsar Samuil, who have nothing more to do with Macedonia than that they just happened to have been born hundreds of years ago on its present territory. And then there is the 25-meter-high equestrian statue, costing about 7.5 million euros, which raises its sword high to attack, and even if it was simply called "Warrior on a Horse," it is clear to everyone that it is supposed to represent Alexander the Great.

In total, about 5 % of the annual GDP was thus used to turn the city into a Disney Land, from which the largely poor population benefits only so mediocre. This is definitely very worth seeing, but if you do not know the background, you can actually go to Disney Land instead.

The highlight of culture and architecture in the town of Bihać is the church of St. Anthony, whose nave was destroyed in World War II, so that only the front with the church tower stands between large old trees and is partly overgrown itself. If you set the church tower photographically well in scene, it almost reminds a little of Angkor Wat.

However, it is not culture and architecture that make the city special. It is the Una, the river that flows through the middle of the city, overcoming countless small waterfalls and also forming various larger and smaller islands. There are no buildings on the islands, yet many are connected by footbridges. So you can walk across the islands and watch the city from park benches in the middle of the Una.

You can also swim in the Una River – either directly in the town center or about a kilometer north of it (at 44.821712, 15.869936). Here a wooden footbridge leads to a whole waterfall front and you can climb along the crest of the falls or just jump into the (amazingly clear) water.

And despite all this, Bihać has apparently remained largely unknown to international tourists.

Prilep is located on the eastern edge of the northern Pelagonian Plain, at the foot of a mountain range that borders the plain, which is about 20 kilometers wide and almost 100 kilometers long. And where Prilep is located, this mountain range is particularly rugged and rocky.

The highlight of the city are “Marko’s Towers”, an old fortress complex of the Serbian King Marko from the 14th century. They were built on or near a pointed, rocky hill directly north of the city. When we hiked the 200 or so meters up the hill in 2022, the ruins lay abandoned: there were no fences, no signs, no tickets, no wardens, no rules. And so one could climb around unhindered on the partly still amazingly well preserved masonry. Finally, from the top of the rock you have a truly spectacular 360° view over the city at your feet, the Pelagonian Plain and the mountain ranges outside.

Prilep is also known for growing tobacco (especially in late summer and fall, tobacco leaves hang everywhere to dry) and for mining the whitest marble in the world (which was also used in the construction of the White House in Washington, but is also used in Prilep to gravel footpaths).

Banja Luka is one of those cities where there is not so much to see, so it is not stressful (and hardly any tourists make it to the city), but still enough that it is not boring.

Apart from the fact that the hostile ethnic groups set fire to each other’s places of worship and destroyed them, the city was largely spared in the Balkan War. Therefore, the newest buildings are probably the mosque and the Orthodox church. Both are of manageable size, but nice to look at and visit. Since we were probably a bit special as tourists, we even spontaneously got a small guided tour of the mosque at that time.

Next to it there is an old fortification, on which you can climb around quite freely, and a market hall with fan T-shirts for more or less venerable autocrats (Tito, Putin, Mladić).

Edirne is nowadays the gateway to Turkey and as such truly not a bad foretaste of Istanbul. Not only that you can get used to the hustle and bustle in the crowded pedestrian zones. Also the Ottoman architecture is already almost as impressive as in Istanbul. After all, Edirne was the capital of the Ottoman Empire for decades before Constantinople was conquered in 1453. So there are mainly large mosques from the 15th and 16th century, which are similarly magnificent as those in Istanbul, but not as crowded (although there are also so many large mosques in Istanbul that by far not all are overrun by tourists). In addition, there are countless old bridges around the city, which open up the same over the rivers Meric and Tunca.

Other Tips

Of course, everyone has these lakes on the note, who travels to the Balkans, nevertheless, here also briefly a word about it: In summer, it is nowadays expensive (around 40 euros) and usually completely overcrowded. The entrance fee is practically only worth it if it’s raining cats and dogs, so that you won’t be pushed over the footbridges by the tourist crowds (and rain isn’t a bad setting at all for the jungle-like scenery). Alternatively, you can visit the lakes for 10 euros in winter. There, perhaps not everything is quite as lush green as in the summer, but still the price-performance ratio is much better.

Enough has certainly already been written about the actual lakes everywhere else: Of course, the landscape is unique, excellently developed with paths and footbridges that are interesting to hike and basically absolutely worth seeing.

Standing on the highest peak of a mountain massif is a pleasure that is usually denied to a cyclist. In the Durmitor massif, however, you can achieve this goal by leaving your bike at your accommodation and lacing up your hiking boots.

Bobotov Kuk is with 2523 meters the highest mountain of the Durmitor massif and it can be climbed in principle also by laymen and without climbing equipment (even if we met some people with climbing helmets and ropes). Unfortunately, the summit was in the clouds when we were there, so we were denied the rewarding view. But even for the thrill of climbing itself, the whole thing was worth it.

In addition, on the way to Bobotov Kuk there are beautiful narrow hiking trails through very varied landscapes: along lakes, through forests and finally up above the tree line, through wide valleys covered with meadows and across rolling fields.

A military sight, through which you can pass by bicycle (or even by car), does not happen every day. A visit to the Željava Airbase is therefore unlikely to be forgotten soon.

The airbase dates back to the 1960s and was built by the Socialist Federation of Yugoslavia in the middle of the border between the republics of Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. Here, high mountains merge in an abrupt bend into a wide, flat plain. And that is exactly what is needed for an underground airport. A network of tunnels was blasted several hundred meters into the mountain, wide enough to accommodate military aircraft and thus park them protected from enemy attack. Various runways begin directly in front of each of the tunnel exits, so that take-offs could be made directly from the tunnels.

During the Yugoslav wars, the Yugoslav People’s Army made the airport unusable and abandoned it. On the Bosnian side it is probably still used as a military training ground, but the Croatian side can be visited by anyone.

We have found various hints on the Internet beforehand, according to which the police allegedly do not like it that you walk around on the airbase or that you should announce a visit in advance to the police. When we were there in July 2022, none of this was necessary and the police (who were definitely present) did not care about us.

And so we were able to cycle unhindered along the two kilometers of deserted runways, climb around on an old bomber and, of course, explore the tunnels. These are unlit and pitch black, and you have to watch out for sudden holes in the floor and steel bars sticking out of the ceiling. But of course, riding a bicycle (or driving a car) around the huge bunkers of an underground military airport is an absolutely unique thing to do!

On the southeastern edge of the Carpathians, hot mud has formed a small lunar landscape. From many small volcanoes and craters the mud bubbles, flows down the cone and finally dries out. If you haven’t been taken by ESA/NASA, but would still like to have pictures of yourself standing on the moon, check this out.

The volcanoes are not overly well known and are probably a bit off the beaten track, so you have a good chance to explore the lunar landscape on your own.

Orheiul Vechi is an Orthodox cave monastery and one of the most important sights of Moldova. The Răut River forms a 180° loop here and in the middle of this loop there is a mountain, which forms a steep rock face on one side and slopes rather flat on the other. And tunnels have now been dug through this mountain: The entrance is on the easy-to-reach flat side of the mountain, but the tunnel goes straight through the mountain and ends at a ledge in the rock face on the other side. This ledge, accessible only through the cave, offers a good view of the river below and the surrounding countryside. The caves themselves are designed as orthodox churches and prayer rooms. If you want to enter the cave rooms, you may have to ask one of the monks to unlock the door to the cave.

| Previous Report | All Reports | Next Report |

Zweiradler Tours: Central Asia Tour

Belinda

Tizian

all Zweiradler Tours • About Us • Support • Contact • Legal Notices

For the licensing of the content of this website and the privacy policy see the legal notices. © 2022 Belinda Benz & Tizian Römer.